I Am Graphics And So Can You :: Part 4 :: Resources Rush The Stage

Part 3 :: I Am Graphics And So Can You :: The First 1,000

An Aside :: I Am Graphics And So Can You :: Motivation & Effort

In the previous article we went through how VkNeo sets up its Vulkan environment... with a few exceptions. It's now time we revisited the things we skipped, and it all deals with resources. Obviously the GPU can't draw anything it doesn't have access to. That would be silly. So how do we get data to the GPU and what does it look like?

Behold the five data types VkNeo will be sending to the GPU. We'll talk about four of these and leave pipelines for another article. If you have some background in graphics, you're aware of the many forms data can take, but you'll also recognize these as the most common elements graphics programmers deal with. If you're new to graphics, don't worry. I'll cover the purpose of each of these in just a moment. But first let's talk about what surrounds us, penetrates us, binds us to... memory it's memory.

Vulkan Memory

Sorry Jesse, it's right over here!!!

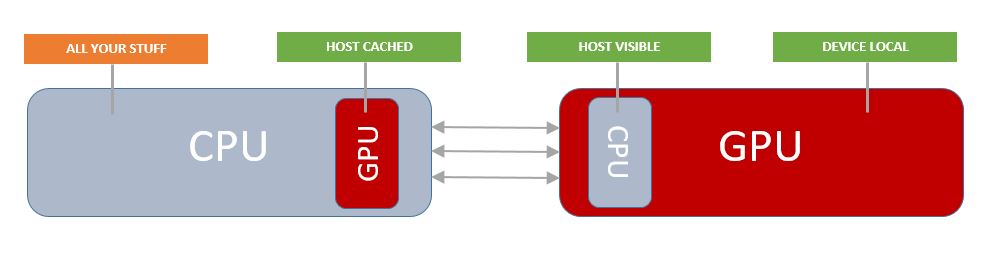

All your data starts off CPU side. In a typical hardware setup both the CPU and GPU maintain a region of memory which can be mapped by the other device. This makes sharing data between the two much easier. Still it's your job ( using Vulkan ) to make it visible to the GPU. Vulkan provides several different types of memory. Note that reading memory across the bus is obviously going to be slower so unless warranted it's best to avoid that whenever ( as long as ) possible.

As always, let's look at some actual data, this time from the extremely useful gpuinfo.org. The site is written and maintained by Sascha Willems, and is a great database for details on graphics hardware info.

Fresh off a GTX 1080. Notice heap indices are shared by multiple memory types.

This is how Vulkan organizes memory. When you call vkGetPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties you get back what amounts to a list of heaps and memory types. When allocating memory, you'll look through this and find a best match for your purposes. Note: There must be at least one memory type with HOST_VISIBLE_BIT and HOST_COHERENT_BIT set. Also there must be one memory type with just DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT set.

HOST_CACHED

Host cached memory means that GPU data is actually cached CPU side. This is useful for when the CPU needs access to data coming off the GPU.

HOST_VISIBLE

Host visible memory can be mapped to the CPU for uploading/updating data. This is very common for uniform buffers as the data contained therein is often updated every frame.

DEVICE_LOCAL

This memory is not visible to the host ( CPU ). It is GPU RAM. It should be the main target of your allocations. If it's not visible to the CPU then how do we get data to the GPU? This is where command buffers come in handy. Vulkan provides special commands to copy data to device local memory. vkCmdCopy*.

HOST_COHERENT

This flag simply means that you don't need to manually flush writes to the device and likewise nothing "special" has to be done to receive write updates from the device.

Note: If you'd like to know more on this subject, head over to gpuopen for a nice write up by Timothy Lottes from AMD.

So now we see that the CPU and GPU work in concert together, how do we do our part? This is where I wrote two custom objects ( globals ) to handle memory management. That would be idVulkanAllocator and idVulkanStagingManager. idVulkanAllocator manages memory allocations while idVulkanStagingManager handles uploading allocations to the GPU.

Let me just interject real quick that recently Adam Sawicki over at AMD came out with a Vulkan Allocator you can drag and drop into your game. As memory management is something "hairy" for a lot of people, just know there are options open to you. I have not had a chance to evaluate it yet, but it's great to have the contribution!

Vulkan can really catch you off guard here. If you remember in Part 3 I briefly mentioned a VKPhysicalDeviceLimits struct? Well amongst the 106 limitations there's one very important one that doesn't readily manifest itself when crossed. This is maxMemoryAllocationCount. That's right, there's an upper bound on how many allocations you can have! At the time of writing my system only supported 4096. That's not much. So what do you do? You actually just allocate in large pools, then sub allocate individual buffers, images, etc from them. Easy peasy right?

idVulkanAllocator

So after the warning above, you can see why a good allocator can save you and your application's life. Now I'll introduce you to managing memory on Vulkan. Primarily this global is a pool allocator. It keeps separate pools for device local memory and host visible. The reason for this is that multiple vkAllocation_t's share the same VkDeviceMemory. Remember we have to sub allocate on our own. Internally each pool manages a linked list of blocks. Neighboring free blocks are merged when possible. If a pool fills up a new one is created. I won't focus so much on the pooling aspect as I will the Vulkan parts.

The implementation of idVulkanAllocator is actually just over 400 lines of code. So apart from the complexity of knowing what's going on with Vulkan, the code is rather straight forward.

No surprises there. Let's continue on with the actual AllocateFromPools.

Allocating for vulkan centers largely around the memory properties you're looking for. That's one reason I went over them explicitly. Now instead of looking at the Allocate function for the pool, we're going to look at the Pool's Init and Shutdown functions. The reason is because Allocate is akin to any run of the mill block allocator you may have seen. And you're here to see Vulkan.

I want to pause a minute and point something out I mentioned from the beginning of this series. Note how the road to get to allocate/free was long and ridden with details? ( Yep who can forget ) But at the parts where the rubber meets the road, the code is lean and mean. This is Vulkan to a T.

So how are the allocations used? I don't want to get ahead of myself, but I think an example is warranted.

Again things are lean and mean. Vulkan actually helps us out by giving us the size, alignment, and memory type bits it expects for a given resource. In this case we just created an image. Every time we create a resource we should ask Vulkan for its memory requirements. This then gets fed to the allocator. The results from the allocator are then used to bind the resource to the vulkan memory!! Pretty exciting eh?

idVulkanStagingManager

The staging manager exclusively handles device local memory. Because we can't map device memory without the host visible bit, we have to use the command buffers to instruct upload that data. Currently in VkNeo, the only vulkan resources that utilize this global system are idImages. Why not just allocate inline? Well this is actually an optimization. We could allocate everything inline, but to do so we'd need to create and destroy a command buffer for each image. We'd also have to manage synchronization for that image work being done. Instead we just allocate a big pool and push multiple images at once. Let's take a look.

The interesting part isn't what's going on inside, but the bits that are using it. And that brings us to our first actual resource. Images.

Image Resources

In Part 3 we actually touched on Vulkan images when we got the SwapChain and created views for it. The thing I didn't go over was actually allocating the image itself, because with the SwapChain the device provides them. Now we'll actually go over the entire allocation process which demonstrates everything we've learned so far in this article.

AllocatE Image

Upload Image

SubImageUpload is called for each image in an idImage. For example a cube image will have six.

So in just two functions we've handled quite a bit of image management and introduced some interesting topics. One thing that really sticks out for Vulkan is the idea of layout transitions. As I mentioned in the code comments, this exists to optimize and restrict how image memory is accessed by various functionality. This fine grain control is part of what makes Vulkan so powerful. Digging into the benefits will take study and experimentation on your part though.

Buffering

Wow we've come a long way already this article. Time for a drink. Aaaahhhh delicious. Now, we've only talked about one type of resource so far. But just like all things Vulkan, the effort is front loaded. The remaining three will go fast because they're all pretty much the same on the application side. These include the Vertex, Index, and Uniform buffers.

All three work in concert to properly represent things you'll see on the screen. Instead of stopping to describe them in detail, let's look at an actual example from VkNeo. Back to RenderDoc!

Let's look at a frame capture of just the shotgun and we'll inspect each of the buffers.

All VkNeo's draw calls are performed with vkCmdDrawIndexed. ( We'll get to drawing in a later tutorial. ) For the image above the call is made with 2337 indices. Let's look at some of the data in RenderDoc.

Vertex & Index Buffers

Click to Enlarge

You'll notice on the top left we have the input data for the vertex buffer. On the upper right are the vertex shader outputs. Each line entry is a shader invocation. idDrawVert is 32 bytes with the first 12 being position data. As I've mentioned before the vertex shader is primarily concerned with positioning things. In the input window you'll see a column labeled in_Position. This is the first 12 bytes of an idDrawVert that was uploaded to the GPU. To the left you'll see two columns VTX and IDX. VTX is the vertex index for the draw call. So zero would be the first. IDX is the actual index number in the index buffer. DOOM 3 BFG is still a "small enough" game that it uses 16 bit indices ( 2 bytes ). That means dealing with index buffers is much cheaper than vertex buffers, and that's why draw indexed calls exist in most graphics APIs; Vulkan being no different.

On the right is the output as I mentioned. Again it has VTX and IDX. Instead of in_Position it has gl_PerVertex.gl_Position. This is the typical output for a vertex location as written by the vertex shader. The indices on the left and right match up so output at zero will always be input at zero. ( Baldur did a bang up job with this interface )

I'll show you how to populate these buffers with data, but first... why did the vertex shader change the position data? Well that's all thanks to a uniform buffer.

Uniform Buffer

Attached to the same vertex shader invocation that gave us the vertex outputs above are two uniform buffers or UBOs. Pictured above is the first. ( The second is a skinning buffer. If you don't know what that is, it's not necessary to understand at the moment. ) The UBO is constant for the length of the draw call.

Again you'll notice Baldur made things super nice by showing the name of each attribute in the buffer. I won't go into each, but notice the 4x lines at the bottom. This is the model-view-projection matrix for the current player's view. This is what's used to transform the vertex data on the left into the vertex data on the right. If you're unfamiliar with matrices or linear alegebra in general don't worry, I'll touch on this a bit when it comes time to talk about drawning ( future article ).

For beginners, don't get too hung up on the names of things. It's all data. It's just data married to a format/layout. Like I mentioned at the beginning of this article, your job is to get it to the GPU. If you know how to allocate, free, map, unmap, and copy memory around, then you're set. The same principles apply here. Just because it has a big name, don't be scared of it. So let's look at how we concretely allocate buffers.

Buffer Objects

This looks awfully similar, yet stunningly simpler than image allocation doesn't it? That's because it is. All three buffer types interact with Vulkan in the same way from VkNeo's perspective. It's application side details that are different, warranting different implementations.

So once we have the buffers, how are they used? Well in VkNeo it's rather simple. Remember vertexCache from Part 3? Well it double buffers frame data consisting of a vertex buffer, index buffer, and uniform buffer ( for skeleton joints, skinning ). This data is backed by the buffer classes like the one I just showed you. Then systems that need to submit data just allocate from the vertex cache and fill on their own. ( guis, model allocation, skinning data, etc )

Congrats on making it through arguably the most boring part of Vulkan! But this is all well and good. It lays the groundwork for the next two articles which will be the most exciting. In them we'll cover pipelines ( shaders, etc ) and rendering itself. So sit tight, grab a drink, and cheers to your success.